A guide to how first-half solutions create second-half suffering

A Jungian map for ambition, meaning, and midlife change

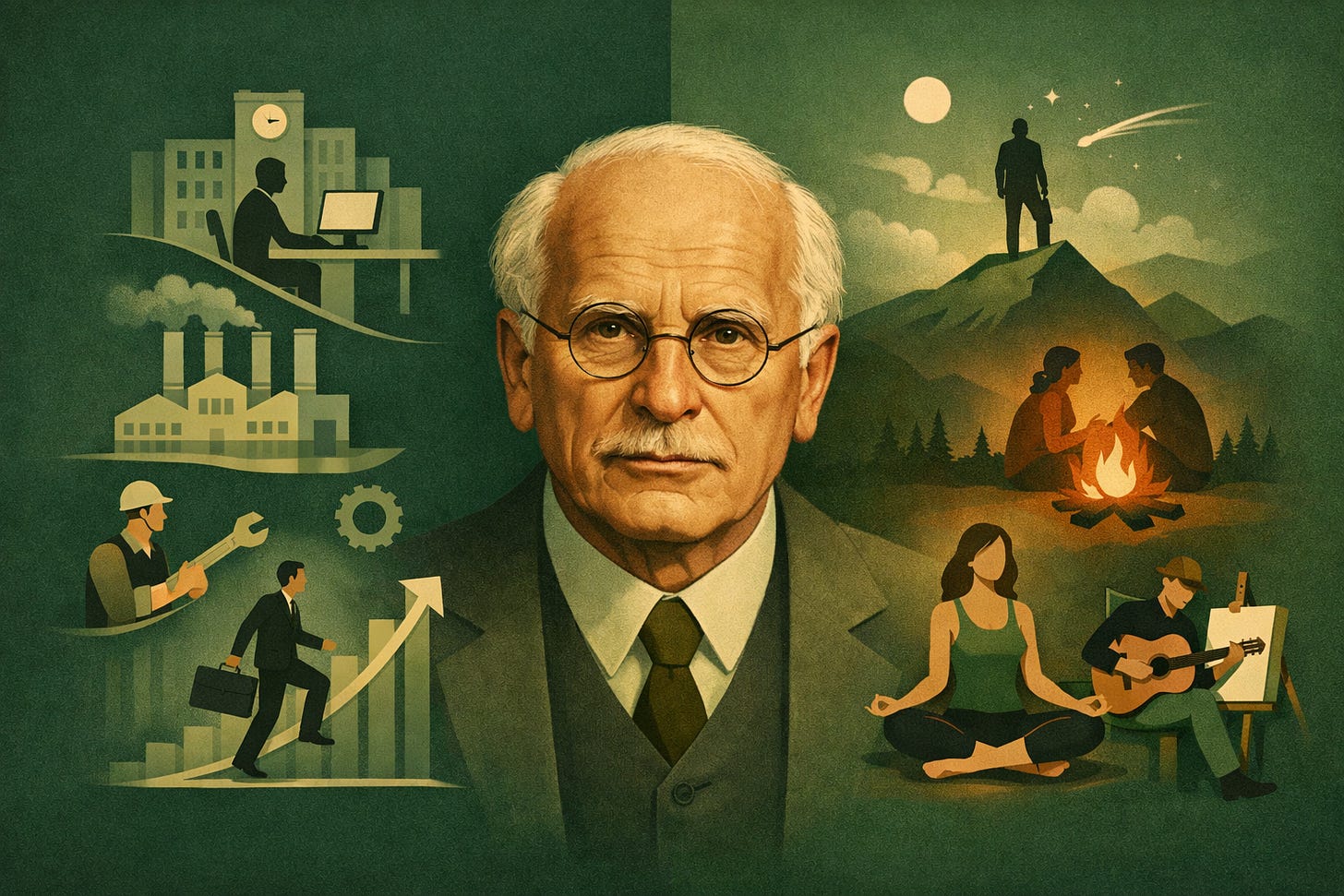

Carl Jung had a theory about life that nobody tells you when you’re young, probably because you wouldn’t believe it anyway.

He saw life as two halves, each with its own work and purpose, and most of the suffering we experience comes from trying to do the second half’s work with the first half’s tools.

The first half of life, roughly until your late thirties or forties, is about building.

You’re constructing an identity, a career, perhaps a family. You’re figuring out who you are in relation to the world. You’re achieving, acquiring, and establishing yourself. This is the time for ambition, for pushing outward, for proving something.

There’s nothing wrong with this. It’s necessary work.

You need to find your place, to test yourself, to discover your capabilities. You need to build the container that will hold the rest of your life. The first half is about saying yes to the world and about becoming somebody.

Then, something clicks!

Usually in your late thirties, your forties, sometimes earlier if life forces it. Jung called it the midlife transition, though it’s not always a crisis. It’s like a knock at the door, a sense that something’s shifted.

The things that used to motivate you don’t quite work anymore. The achievements feel hollow. The identity you built so carefully starts to feel like a costume. You look at your life and think: “Is this it? Is this what I was working toward?”

This is when the second half begins, whether you’re ready or not.

The second half of life, Jung argued, isn’t about building anymore. It’s about deepening. Not expansion, but integration. Not achieving, but becoming.

This is when you stop asking “What do I want to be?” and start asking “Who am I, really?”

The work now is internal. It’s facing the parts of yourself you ignored while you were busy succeeding.

The shadow, Jung called it. All the qualities you rejected, the paths you didn’t take, the aspects of yourself that didn’t fit the image you were creating.

In the first half, you become who you think you should be. In the second half, you become who you actually are.

This sounds mystical, but it’s remarkably practical. It’s the successful businessman who suddenly wants to paint or the devoted mother who rediscovers herself after the children leave.

The achiever begins to question whether any of it mattered.

The second half asks you to make peace with what you’re not. To accept your limitations, to forgive yourself for not being everything, and to integrate the parts you rejected.

It’s also when you start facing mortality, really facing it. Not as an abstract concept but as a personal reality, and strangely, this awareness doesn’t diminish life; it deepens it.

Things matter more when you know they’re finite.

As Jung said, People try to solve second-half problems with first-half solutions.

Feeling empty? Achieve more. Feeling lost? Build something bigger. Feeling disconnected from yourself? Stay busier.

You can’t build your way out of an integration problem. You can’t achieve your way to wholeness.

The second half requires different skills: reflection, subtraction, and being rather than doing.

This doesn’t mean you stop working or creating. It means the motivation changes. You’re no longer trying to prove something to the world. You’re trying to express something true about yourself.

Jung believed this transition was crucial for a meaningful life.

The people who never make it, who cling to first-half values into old age, become bitter or desperate. They’re still trying to achieve when they should be learning to accept, and still trying to become when they should be learning to be.

So where does this leave you, right now?

If you’re in the first half, build well. But build consciously. Don’t sacrifice everything for success. Don’t ignore the parts of yourself that don’t fit your ambition because you’ll need to come back to them later.

If you’re in the transition, trust it. The emptiness you feel isn’t failure; it’s an invitation to depth. The questions you’re asking aren’t signs you’ve wasted your life; they’re signs you’re finally living it.

If you’re in the second half, let go of proving or perfecting. You’ve built enough. Now the work is to inhabit what you’ve built, to integrate who you’ve been, to become whole.

This is amateur Jungian psychology, simplified and rough. The core insight remains: life has seasons, and each requires different work.

If I am to leave you with one thing, learn to recognize which season you’re in. Then do that season’s work.