How discipline becomes its form of inspiration

Discipline is the host who makes sure the party happens, whether the guest arrives or not.

Stephen King writes in “On Writing” that “Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration; professionals just get to work.”

I used to hate that quote. It sounded like productivity propaganda: the grinding imperative to always produce, the idea that waiting for the right mood is weakness, and the claim that real artists suffer through a lack of inspiration rather than honoring their creative rhythms.

Then I spent almost two years waiting for inspiration to write.

Not literally waiting, I’d tell myself I was living, gathering experiences, letting ideas percolate. But actually, I was avoiding the desk. Because sitting down to write without feeling inspired felt like betraying the art. Like I’d produce something mechanical and lifeless, a simulacrum of real writing that only happens when the muse arrives.

So I waited. The muse was busy elsewhere.

Finally, out of desperation more than wisdom, I made a rule: write every morning at six, regardless of how I feel. Not write well. Not write-inspired material. Just write.

The first weeks were exactly as bad as I feared. I produced garbage. Lifeless sentences about nothing. Pages that even I didn’t want to read. Every session confirmed my belief that writing without inspiration creates worthless work.

But I kept going. Because at that point, producing worthless work was better than producing no work.

Then something strange happened around week four. I sat down uninspired, started writing the usual garbage, and somewhere in the middle of the third paragraph, something shifted. An idea I didn’t know I had appeared. A connection I hadn’t seen formed. The writing went from mechanical to alive.

Not because inspiration struck. Because the discipline of showing up created the conditions where inspiration could find me.

We’ve got inspiration backward.

We think: first comes inspiration, then comes work. The feeling of inspiration is the signal that it’s time to create. Without that feeling, creating is pointless; you’re just going through motions.

But watch what actually happens to people who wait for inspiration: they create sporadically or not at all. Inspiration comes when it comes, which is infrequently and unpredictably. Their output depends entirely on a feeling they can’t control.

The professionals—the ones who actually produce—have learned that it works in reverse. First comes discipline. The work creates the inspiration, not the other way around.

“You can’t wait for inspiration. You have to go after it with a club.” — Jack London

Inspiration is a feeling that occurs during engaged work, not before it.

This is the insight that changes everything. Inspiration isn’t the condition that makes work possible. It’s the feeling that sometimes arises when you’re already working.

You sit down uninspired. You start working anyway. You write bad sentences, sketch rough lines, and play wrong notes. Then, sometimes, not always, the work itself generates the feeling of inspiration. Your brain warms up. Ideas connect. You get interested in what you’re doing.

When I wait for inspiration before writing, I can wait weeks. When I write without waiting for inspiration, it often shows up twenty minutes into the session. Not because I earned it through suffering, but because the act of working created the mental state where inspiration becomes possible.

Discipline creates reliability that inspiration never can.

Inspiration is fickle. It arrives unannounced. It leaves one unexpected. It’s wonderful when it’s present, but completely unreliable as a production strategy.

Discipline is boring. It’s the same time, the same place, and the same commitment, regardless of how you feel. But it’s reliable. You show up at six every morning, whether you feel like it or not. That reliability accumulates into actual output.

The myth tells us that inspiration produces the best work. But the reality is that consistency produces the most work, and volume creates the quality opportunities.

I produce maybe one good essay for every five I write. If I only write when inspired, I might write five essays a year, yielding one good one. If I write consistently, I write fifty essays a year, yielding ten good ones.

The discipline doesn’t improve each piece. It multiplies opportunities for something good to emerge.

Discipline becomes its own form of inspiration through momentum.

This is the part no one tells you: after a while, the discipline itself starts to feel inspiring.

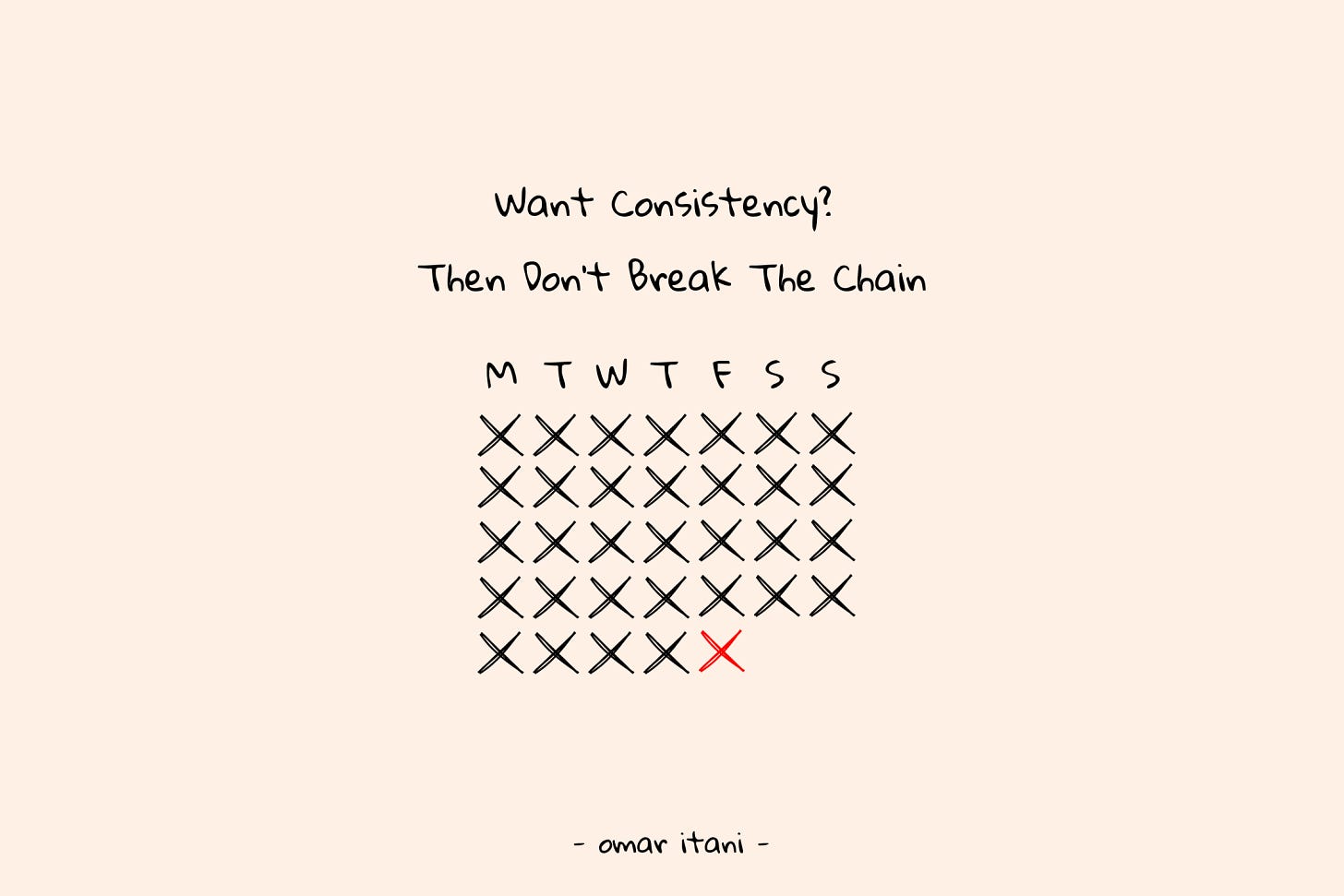

Not in the sense that you wake up excited to work every day—you often don’t. But in the sense that the streak itself becomes meaningful. You’ve written for a hundred days straight. You don’t want to break the chain. That commitment generates its energy.

The comedian Jerry Seinfeld describes his productivity method: “Don’t break the chain. Mark an X on the calendar every day you write jokes. Your job is not to break the chain of X’s. After a while, the chain itself becomes the motivator.”

That’s not externally sourced inspiration. That’s discipline generating internal momentum that functions like inspiration; it gets you to the desk when you don’t feel like going.

The myth of inspiration protects us from the fear of being mediocre.

This is the uncomfortable truth: we cling to the inspiration myth because it protects our ego.

If I only write when inspired, then everything I write can be good. If it’s not good, I just wait longer for better inspiration. I never have to face the fact that I’m capable of producing mediocre work.

But if I write every day regardless of inspiration, I have to confront my mediocrity regularly. Most days, the work is fine. Some days it’s bad. Occasionally, it’s good.

That’s humbling. It means I’m not a misunderstood genius waiting for the right inspiration. I’m a regular person who sometimes does decent work through the unglamorous process of showing up repeatedly.

The writer Anne Lamott calls them “shitty first drafts,” the terrible versions you have to write to get to the decent versions. But you only write those shitty first drafts if you’re working with discipline, not waiting for inspiration to deliver you perfect first drafts.

Discipline doesn’t kill creativity; it creates the container in which creativity can function.

The myth says structure and routine stifle creativity. Creativity needs freedom, spontaneity, and a slow pace to breathe.

But watch what happens to people with complete freedom and no structure: they produce very little. The infinite possibility paralyzes. Without constraints, without routine, without discipline, the creative impulse dissipates into vague intention.

Discipline provides constraint. Same time. Same place. Same commitment. Within that container, creativity can actually operate.

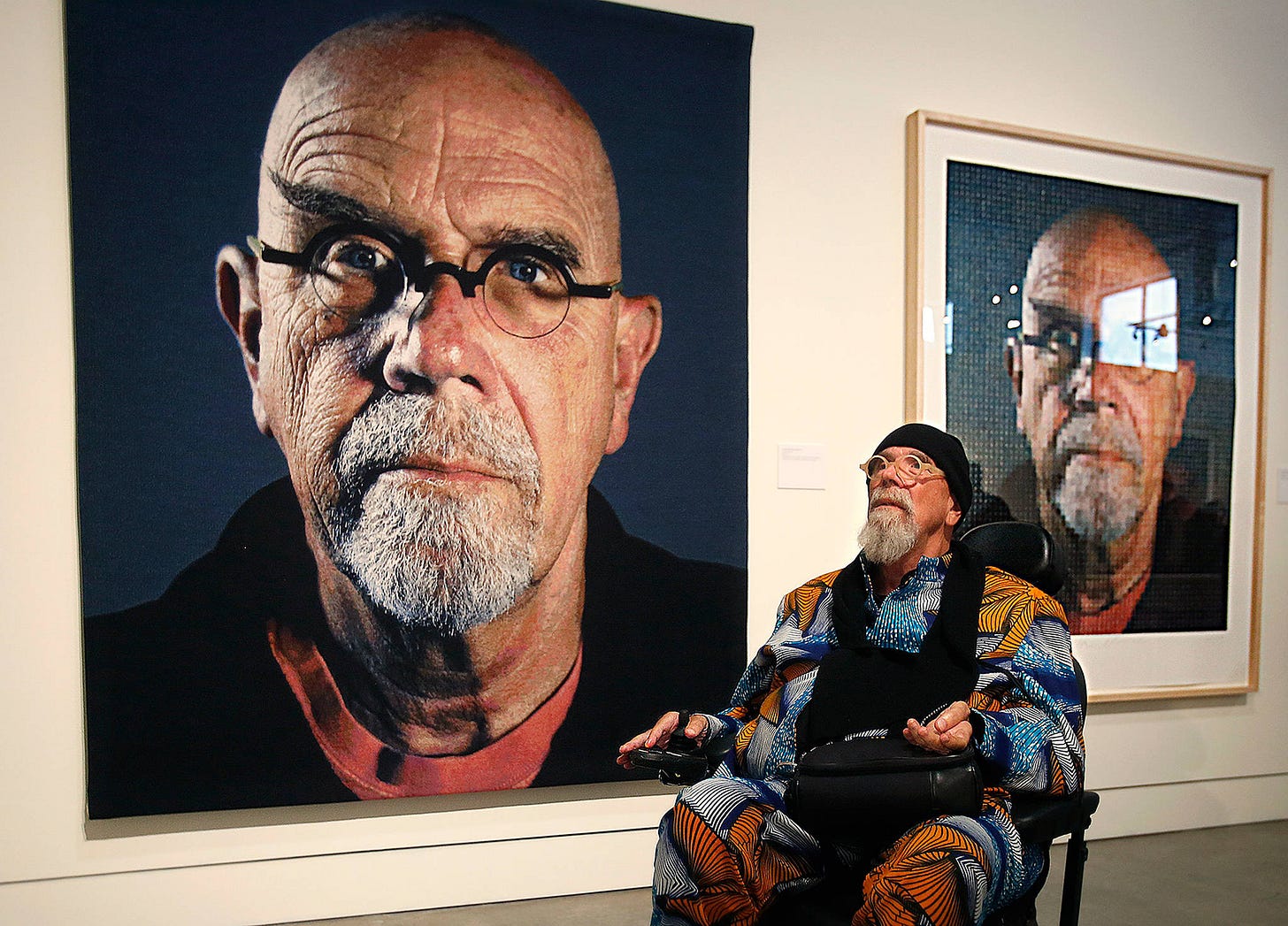

The painter Chuck Close, who created large-scale photorealistic portraits, said, “Inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us just show up and get to work.”

He wasn’t dismissing inspiration. He was locating it accurately, as something that shows up after you’ve already started working, not before.

The transition from inspiration-dependent to discipline-driven is uncomfortable.

When you start working with discipline instead of waiting for inspiration, there’s an adjustment period that feels terrible.

You’re producing work that doesn’t feel inspired. You’re showing up when you don’t want to. You’re creating without the emotional validation that inspiration provides. It feels like you’re betraying something, your art, your authentic self, your creative integrity.

Push through that. The discomfort is just your brain adjusting to a new mode. You’re learning to work from discipline instead of feeling, and that feels wrong at first because it’s unfamiliar.

But eventually, not immediately, but eventually, the discipline starts generating its own satisfaction. Not the high of inspiration, but the steadier satisfaction of showing up, of keeping commitments to yourself, of seeing accumulating output.

Inspiration still happens. It just happens during work, not before it.

None of this means inspiration disappears. It means you stop waiting for it to arrive before you begin.

When you work with discipline, you still have inspired sessions. Days when everything flows, when ideas connect brilliantly, and when the work feels effortless. Those days are wonderful.

The difference is that you also have uninspired sessions. Days when nothing flows, when you’re just grinding through. And you work through those days knowing that tomorrow might be better, or it might not, but you’ll show up either way.

The inspired days become bonuses within a practice that doesn’t depend on them. Instead of a prerequisite for working, inspiration becomes an occasional gift that makes work more enjoyable.

Going from “Do I feel inspired?” to “Is it time to work?”

This is the operational difference. When inspiration governs, you check in with your feelings: Do I feel inspired? Am I in the mood? Is this the right energy?

If the answer is no, you don’t work.

When discipline governs, you check the clock: Is it time to work? If yes, you work. How you feel about it is irrelevant data.

That sounds harsh. It’s actually liberating. You’re not responsible for generating the right feelings before you can work. You’re just responsible for showing up.

Whether the session is good, bad, inspired, or mechanical isn’t determined by how you feel before you start. It’s determined by what happens during the work itself.

The myth persists because inspiration feels more romantic than discipline.

The story of the inspired genius, struck by vision, creating masterpieces in fits of creative frenzy, that’s compelling. It makes creativity seem magical, special, and touched by something beyond the ordinary.

The story of the disciplined creator, showing up at the same time every day, producing mostly decent work through sheer consistency, that’s boring. It makes creativity seem like any other job. Which is it?

But we resist that because it deflates the mythology. If creativity is just discipline, then what makes creators special? If inspiration is simply what sometimes happens during disciplined work, then where’s the magic?

The magic is in the work itself, in what gets created through consistent effort over time. Not in how you feel before you start.

The experienced creator knows that inspiration is unreliable and discipline is dependable. They’ve learned that waiting for inspiration means waiting indefinitely, and showing up despite a lack of inspiration means actually creating things.

When you’re waiting for inspiration to start, you’re probably just avoiding the work.

What would happen if you showed up anyway? If you started without the feeling that you think you need? If you let discipline carry you until inspiration decides to join?

Are you honoring your creative rhythms, or are you hiding from the discomfort of creating when you don’t feel like it?

Inspiration is a guest that sometimes shows up at the party. Discipline is the host who makes sure the party happens, whether the guest arrives or not.

Everything else is just waiting for a feeling that might never come, while calling that waiting artistic integrity.