The inability to speak your emotions is not a failure of character.

Write your way through the silence until you see

I suspect you know the feeling I am about to describe. It is a specific kind of heaviness. It sits right at the base of the throat, or it may be a tightness in the chest. You are filled with an emotion so vast or so complex that when you open your mouth to explain it to someone, nothing comes out. The words feel dry and inadequate, or they vanish altogether.

We often judge ourselves quite harshly for this. We think, ‘I am an adult; I should be able to articulate how I feel.’ But I want to start by offering you some reassurance. This inability to speak your emotions is not a failure of character. It is often a matter of biology.

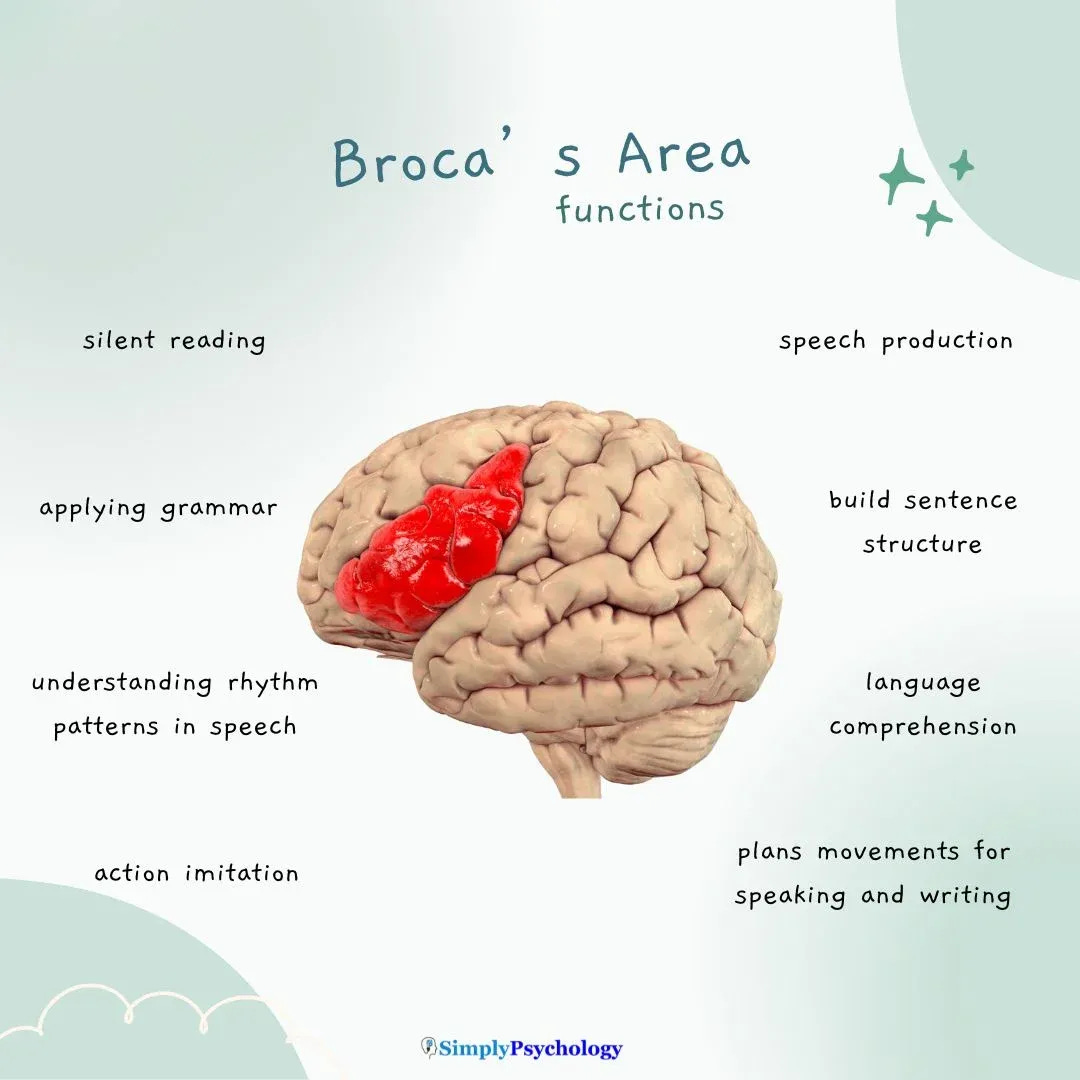

There is a fascinating phenomenon that happens when we are overwhelmed. Neuroscientists have observed that when we are in the grip of intense emotion or trauma, the area of the brain responsible for speech—Broca’s area—can actually shut down.

Literally, the power goes out in the language centre. At the same time, the emotional centres of the brain are lighting up like a Christmas tree. So, quite physically, you are feeling everything and saying nothing because the bridge between the feeling and the speaking has collapsed.

So, how do we write about emotions when our voice has failed us? How do we bypass that collapsed bridge?

We should not need to repair the bridge immediately. Instead, we can take the side door. We can use writing not to report on our feelings, but to translate them into something tangible.

Start with the Body

If you cannot find the name of the emotion, do not force it. Do not worry about whether it is sadness, grief, or melancholy. Those are abstract labels, and the part of you that is hurting is not interested in labels. It is interested in sensation.

The psychologist Eugene Gendlin spoke of something called the ‘felt sense’.

This is the murky, physical awareness of a situation before we have words for it. When you sit down to write, I want you to bypass the emotion and go straight to the body.

Ask yourself: ‘If this feeling were a physical object located inside me, where would it be?’

Write about the heat in your face. Write about the way your stomach feels like a knotted rope. Write about the temperature of your hands. You might write a sentence like, ‘My shoulders are pulled up so high they are touching my ears, and there is a stone in my gut that feels cold.’

Do you see what has happened there? You haven’t used a single emotional word. You haven’t said ‘anxious’ or ‘afraid’. Yet, you have communicated the emotion perfectly.

You have taken the feeling out of the nebulous realm of the mind and grounded it in the reality of the body. By writing the physical symptom, you are validating the emotional cause.

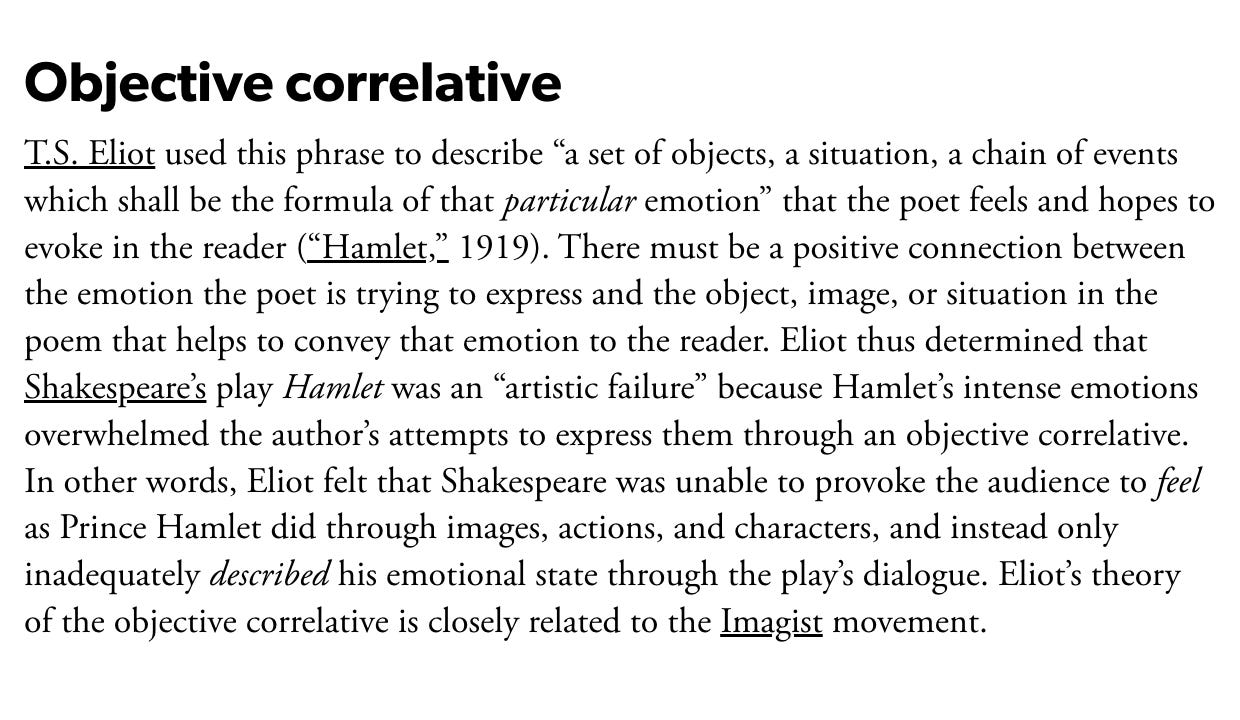

Once we have grounded ourselves in the body, we can look outward. There is an excellent concept in literary theory introduced by T.S. Eliot called the ‘objective correlative’. It sounds terribly academic, but the idea is beautiful and very practical for our purposes.

The theory is that the only way to express emotion in art is by finding a set of objects, a situation, or a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion.

In simpler terms, instead of trying to describe the feeling directly, you describe an object or a scene that feels the way you do.

If you cannot say ‘I feel lonely and neglected,’ you might look out the window and describe a singular, rusted swing set in an overgrown garden. You might tell a cup of tea that has gone cold on the counter, with a skin forming on the milk.

When you write about the cold tea or the rusted swing, you are actually writing about yourself. But you are doing it safely. You are projecting the internal state onto an external object. This creates psychological distance, making the emotion manageable. It is easier to describe a storm outside the window than the storm inside the heart, even though we are talking about the same turbulence.

Finally, I want to talk about the pressure to make sense.

When we speak to others, we are socially conditioned to be coherent. We need to speak in complete sentences. We need to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. This pressure is often what silences us. We think, ‘I can’t explain this clearly so that I won’t say anything at all.’

The page makes no such demand on you.

The page does not require grammar.

It does not require logic.

If you are struggling to voice your emotions, permit yourself to write in fragments. Write a list. Write a series of disjointed words. Write the same word twenty times if that is what the rhythm of your anxiety demands.

There is a freedom in incoherence. When you stop trying to compose a narrative and let the debris of your mind fall onto the paper, you often find the truth hiding in the mess. You might find that among the chaos, one sentence stands out that surprises you. You might look at it and think, ‘Oh. So that is what I have been carrying.’

Writing, in this sense, is an act of listening to yourself. It is becoming the witness to your own experience.

You do not need to be a poet. You do not need to be a scholar. You need to be willing to sit with the discomfort of silence and trust that your hand knows what your voice does not.

There is a quote by the author Flannery O’Connor that I cherish. She said, ‘I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.’

That is the invitation I offer you today. Do not wait until you have the perfect words to start writing. Write to find the words. Write about the lump in the throat, the cold tea, the grey sky. Write your way through the silence until you see, to your own surprise, that you have been speaking all along.

Thank you for reading. Your time and attention mean everything. This essay is free, but you can always buy me coffee or visit my shop to support my work. For more thoughts and short notes, please find me on Instagram.