Confusion is not failure; it is the mind asking for a slower pace.

The hardest part of anxiety is explaining a storm that only you can feel.

You’re lying in bed at three in the morning. You’re catastrophising.

You’re running through every possible disaster. You’re convinced something terrible is about to happen. And you can’t stop. You can’t turn it off.

Your body is flooded with cortisol and adrenaline, and all the ancient systems that are meant to keep you alive are screaming: DANGER. DANGER. DANGER.

And in the meantime, nothing is actually dangerous. You’re safe. You’re in your bed. There’s no actual threat. But your nervous system doesn’t believe that. Your nervous system has decided that this is an emergency. And it will not be reasoned with.

This is the thing about anxiety that makes it so confusing. It’s an entirely unreasonable response to a reasonable situation. It’s urgency masquerading as logic. It’s your survival instincts firing at the wrong target.

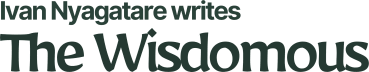

The neuroscientist Bessel van der Kolk has researched how the anxious brain works. And one of the most interesting things she’s found is that anxiety isn’t actually about the future.

It feels like it is. It feels like you’re worried about something that might happen. But actually, anxiety is your body’s response to a perceived threat in the present.

Your nervous system has scanned the environment and decided: this is dangerous. Not logically. Not rationally. But somatically. Your body has decided this is dangerous.

And your conscious mind, the part of you that can reason and think and look at actual evidence, your conscious mind comes in after the fact and tries to construct a narrative about why you’re anxious.

It looks around for a threat. And it finds something. Or it constructs something. And now you’re convinced that you’re eager about that specific thing.

But you’re probably not. You’re probably anxious because you’re tired. Or because you didn’t eat enough. Or because you drank too much coffee. Or because someone said something that reminded you of something from years ago that you haven’t fully processed. Or because your nervous system is just running hot today for reasons that have nothing to do with logic.

And your anxious brain grabs onto that nothing and makes it everything. You’re worried about your health.

You’re concerned about your relationship. You’re worried about whether you said something weird in that conversation six months ago.

You’re concerned about climate change. You’re worried about being anxious, which makes everything worse.

The psychologist Albert Ellis talked about how anxiety often comes from what he called “catastrophising”, the tendency to imagine the worst possible outcome and then treat that imagined outcome as though it’s inevitable.

You have a slight ache, and you immediately go to: I have cancer. You feel awkward in social situations and immediately think, “Everyone hates me.” I’ll never have friends.

I said something mildly critical, then immediately added, “I’ve destroyed this relationship irreparably.”

And the confusing part is that these narratives feel completely real whilst you’re in them. They feel like predictions. They feel like facts. They feel like things that are definitely going to happen. But they’re not. They’re just your anxious brain playing out scenarios.

The trauma-informed therapist Resmaa Menakem talks about anxiety as something that gets stored in the body. It’s not just a thought. It’s a physical state. Your nervous system is activated. Your muscles are tense.

Your breathing is shallow. Your digestion has shut down. Your body is literally preparing for a threat that doesn’t exist.

And no amount of rational thinking is going to fix that whilst your body is in that state. Because the thinking brain and the feeling brain aren’t the same thing. You can tell yourself logically that everything is fine. Your body doesn’t listen. Your body keeps screaming danger.

This is why anxiety is so confusing. Because you can know, you can actually, genuinely know, that there’s nothing wrong. Everything is fine.

You’re safe. And yet you still feel terrified. And that disconnect between what you know and what you think is maddening.

The CBT approach to anxiety tries to fix this by changing your thoughts. If you change the thoughts, the theory goes, the feelings will follow. Think your way to calm. Reason yourself out of anxiety.

And sometimes this works. Sometimes, catching yourself catastrophising and reality-checking the narrative can help. Can interrupt the spiral.

But sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes you’re too deep in it. Sometimes your nervous system is too activated.

Sometimes the rational argument bounces off the irrational panic, and nothing changes. You’re still terrified. And now you’re frightened and also frustrated that you can’t think your way out of it.

Which makes it worse. Because now you’re anxious about your anxiety. You’re panicking about the panic.

You’re frustrated that you know better, and yet you can’t control this.

And that’s the most confusing part of anxiety. That self-awareness that accompanies it. You know you’re being irrational. You know there’s no actual threat. You can see the absurdity of your own mind. And yet you can’t stop it.

The psychologist Roy Baumeister discusses a theory called “ironic process theory.”

It’s the idea that trying not to think about something makes you think about it more. If I tell you not to think about a white elephant, what do you think about? A white elephant.

And anxiety works the same way. You’re anxious, and you tell yourself not to be worried. This makes you more aware of the anxiety.

Which triggers more anxiety? Which triggers more panic about the anxiety? And now you’re in a feedback loop created by your own awareness.

The only way out of this loop is to stop fighting it. To stop trying to think your way out. To stop resisting the feeling.

And that’s counterintuitive. That’s the opposite of what you want to do. Because what you want to do is escape the feeling. What you want to do is make it stop. But the faster you try to make it stop, the longer it sticks around.

The acceptance and commitment therapy approach to anxiety suggests something different. Instead of trying to get rid of the anxiety, you learn to feel it without being controlled by it.

You acknowledge that it’s there. You don’t try to fix it. You don’t judge it. You just let it be present whilst you do what matters to you anyway.

Which sounds simple and is actually very hard.

Because anxiety is designed to stop you, it’s designed to make you freeze. It’s designed to keep you safe (from threats that don’t actually exist). And overriding that isn’t easy.

The therapist Steven Hayes calls this “cognitive fusion”, the tendency to believe your thoughts. You have the thought: Something bad is going to happen. And you fuse with it. You believe it. It becomes your reality.

And the way out is to “defuse” from it. To see the thought as a thought. To notice it’s something your brain produced. But not necessarily something true.

This is where the confusion gets really interesting because anxiety lies to you. Constantly. It tells you things that aren’t true, and your nervous system responds as though they are true.

But here’s the thing: you can’t tell when anxiety is lying. In the moment, everything it says feels true. The catastrophe feels imminent. The danger feels real. The shame feels justified. The loneliness feels permanent.

And there’s no way to fact-check it in real time. You can’t calmly evaluate whether the thing your anxiety is screaming about is actually going to happen. You’re too activated. You’re too in it.

So you have to trust, on faith, almost that anxiety lies. That most of the things it catastrophises about don’t happen.

The feeling of impending doom is not an accurate reflection of reality. Just because you feel sure something bad is going to happen doesn’t mean it will.

The author Douglas Adams wrote, “The answer to the great question of life, the universe and everything is 42.”

He was joking, of course. But there’s something in there about how we’re always looking for the answer, always searching for certainty, always wanting to know.

And anxiety takes advantage of this.

It pretends to have answers. It’s certain. It’s convinced. Surely, disaster is coming. And that certainty is compelling. It feels like knowledge.

It feels like you’re seeing something others aren’t. And that feels powerful, even though it’s actually destroying you.

So the confusing thing about anxiety isn’t just the anxiety itself. It’s as if anxiety is trying to help.

It seems like it’s keeping you safe. It looks like it’s giving you essential information. And sometimes it is. Sometimes anxiety is actually worth listening to.

But most of the time? Most of the time, it’s just noise. It’s a false alarm. It’s your nervous system misfiring.

And you can’t tell the difference. Not in the moment. Not when you’re in it.

Not when your body is flooded with stress hormones and your mind is running through worst-case scenarios.

All you can do is sit with it. You can accept that this is what’s happening right now. This is what your nervous system is producing. It’s not

comfortable. It’s not pleasant. But it’s not dangerous. The feeling itself is not dangerous.

You’re anxious, and that’s OK. You’ll be OK. You might feel terrible for a while, but you’ll be OK.

And eventually, if you don’t fight it, if you don’t fuel it with more worry, it will pass. Your nervous system will recognise that the threat isn’t coming.

Will realise it was a false alarm. Will gradually downregulate. And you’ll be left in the wreckage of all that pointless fear, wondering: why does my brain do this to me?

And the only honest answer is: sometimes nervous systems are confused. Sometimes they malfunction. Sometimes they’re so dedicated to protecting you that they overdo it.

And there’s no way to fix that completely. There’s no way to make anxiety go away forever. There’s no permanent solution. Anxiety isn’t a problem to be solved; it’s a feature of being human, a feature that misfires too often, but a feature nonetheless.

The confusion persists. The irrationality of it never quite makes sense. Even after you’ve learned about it, even after you’ve read the research. Even after you’ve lived with it for years.

Because anxiety, fundamentally, is just your brain trying to protect you from a danger that doesn’t exist. And that isn’t very clear. It will always be confusing. The best you can do is learn to tolerate the confusion.

Learn to sit with the irrational panic and not let it drive your decisions. Learn to move forward even when your nervous system is screaming that you shouldn’t.

And know that you’re not broken. Your nervous system is just extremely anxious. About everything. All the time. And that’s OK. You can live with that.

It isn’t very clear. But you can live with confusion.

Thank you for reading. Your time and attention mean everything. This essay is free, but you can always buy me coffee or visit my shop to support my work. For more thoughts and short notes, please find me on Instagram.