Why we must narrow our world to change it.

You are no longer a scattered beam of light; you are a laser.

I want to speak to you today about the architecture of your attention. If you are anything like the people I usually talk with, creative, ambitious, and deeply curious, I suspect your mind often feels like a browser with fifty tabs open.

You are likely juggling three different major projects, trying to learn a new language, maintaining a social life, and perhaps thinking about writing a book, all at the same time.

It is a seductive state of being. We live in a culture that valorises the ‘polymath’ and the ‘multitasker’. We are told to cast our nets wide, to be well-rounded, and never to miss an opportunity.

But I want to offer you a counter-proposition, one that might feel uncomfortable at first. If you genuinely wish to make a dent in the world or even just in your own life, your focus needs to be radically deep and ruthlessly narrow.

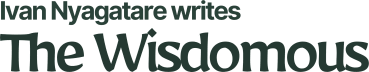

Let’s look at this through a simple lens of physics. Think of the formula for pressure: Pressure equals Force divided by Area.

You only have a finite amount of Force. Your energy, your cognitive bandwidth, and your hours in the day are limited resources. If you apply that Force over a wide area, trying to move five massive projects forward simultaneously, the pressure you exert on any single point is negligible. You are merely dusting the surface of five different things. You might make a millimetre of progress on all of them, but you will not break through on any of them.

Now, imagine taking that same amount of force and concentrating it onto a pinhead. That is a deep, narrow focus. That is the kind of pressure that pierces through resistance. It is the difference between sunlight, which warms the earth, and a laser, which can cut through steel. Both are light; the only difference is the width of the focus.

I know what you might be thinking. You might be thinking, ‘But I am good at multitasking. I can handle the variety.’

I say this with great affection, but you are likely lying to yourself. The human brain is not designed for parallel processing of complex tasks; it is intended for serial processing. When we flip between projects, answering an email for Project A, then writing a paragraph for Project B, we incur what Sophie Leroy, a business professor, calls ‘attention residue’.

When you switch tasks, your attention does not follow you immediately. A part of your brain remains stuck on the previous task, churning over the unfinished problem. If you are constantly widening your focus, flitting from one interest to another, you are essentially walking around with a brain full of fragmented residue. You are never fully present with the work in front of you because you are still subconsciously processing the work behind you.

This is why ‘wide’ focus often feels so exhausting. It is not the work itself that tires you; it is the constant, expensive tax of switching contexts.

So, why do we do it? Why do we keep our focus wide if it is so inefficient?

The answer is emotional. Keeping our options open feels safe. Narrowing our focus feels like a loss.

Choosing one project is rejecting four others. To say, ‘I am going to spend the next six months writing this novel and nothing else,’ is to mourn the painter, the runner, and the entrepreneur you also wanted to be during those six months.

Narrow focus requires a bit of grief. You have to be willing to kill your darlings. You have to be willing to look at a perfect opportunity and say, ‘No. Not because it isn’t worthy, but because it isn’t this.’

This is where your intention must be strongest. It takes immense courage to be narrow. It is far easier to be broad and shallow because if you fail at one of ten things, it doesn’t hurt as much. But if you commit to one thing, if you go deep, you are all in. The vulnerability is higher, but so is the potential for mastery.

I want you to visualise a farmer searching for water. He digs ten holes, each of them three feet deep. He works incredibly hard. He is exhausted at the end of the day. But he finds no water.

His neighbour digs one hole, thirty feet deep. She finds the water.

This is how I want you to look at your projects. When you spread your focus wide, you are digging shallow holes. You are busy, yes. You are hardworking, certainly. But you are not reaching the water table.

Deep work, the kind of narrow, obsessive focus I am advocating for, is where the value lives. It is in the depths that you find nuance, complex solutions, and the flow state that make work feel like play. You cannot reach that state if you are checking your phone every twenty minutes or worrying about the other three projects on your list.

So, how do you apply this?

I am not suggesting you must abandon all your interests forever. I am suggesting you serialise them.

Permit yourself to be monomaniacal for a season. Pick the one project that, if completed, would make the others easier or irrelevant. Pour your ‘force’ into that singular ‘area’. Let the other gardens go a bit weedy for a few months. The world will not end if you are not making progress on everything at once.

There is a profound peace to be found in the narrow. When you stop trying to be everything to everyone and stop trying to do everything at once, the noise in your head quiets down. You are no longer a scattered beam of light; you are a laser.

And that, my friend, is how you cut through the noise. That is how you finish the work that matters.

Thank you for reading. Your time and attention mean everything. This essay is free, but you can always buy me coffee or visit my shop to support my work. For more thoughts and short notes, please find me on Instagram.

Loved this framing! The pressure formula realy clicked for me, especially since I've been spreading myself too thin across client projects lately. That farmer analogy is spot-on - I've defintely been digging those shallow holes. The hardest part for me is actually letting the other gardens go weedy, but I'm starting to see it's not abandonment, it's strategic sequencing.