You Can’t Outwork Someone Devoted to a Better Thing

Working hard on the wrong thing is still working hard, but it’s a slow form of failure, made worse by the fact that it feels like progress.

We have been sold a comforting lie about success: if you work harder than everyone else, you’ll win. Stay up later, wake up earlier, hustle more intensely, and eventually you’ll outpace the competition through pure effort.

It’s a seductive narrative because it puts everything in your control. You don’t need luck, connections, or talent. Just work ethic. Just grit.

The reality is that you cannot outwork someone who’s working on a fundamentally better thing than you are. No amount of effort can overcome a directional mistake.

The Efficiency Trap

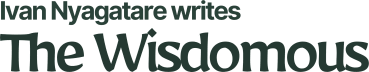

Let’s imagine two people. Person A is working 80 hours a week building a better typewriter. Person B is working 40 hours a week building a computer. Person A is dedicated, disciplined, and intensely focused. They’re optimizing every detail, streamlining every process, and absolutely maximizing their productivity.

Person B still wins. Not because they worked harder, but because they were working on something better. You might argue about which is better, but the computer offers more value and has the typewriter function built in.

This is the efficiency trap. We become obsessed with doing things efficiently without pausing to ask whether we should be doing them at all. We optimize our workflow, eliminate distractions, and take pride in our productivity. Meanwhile, someone else is working on a different problem entirely, rendering all our efficiency irrelevant.

The trap is particularly dangerous because hard work feels virtuous. When you’re putting in the hours, making sacrifices, and pushing through difficulty, you feel like you’re doing something meaningful. And you are. But if you’re running in the wrong direction, speed doesn’t help.

Direction Over Speed

There’s a concept from computer science called computational complexity. Some problems are inherently easier to solve than others. If you’re working on an issue with exponential complexity and someone else is working on a problem with linear complexity, you will lose even if you’re ten times faster, a hundred times smarter, or a thousand times more dedicated.

The same principle applies to everything. Some career paths have more leverage than others. Some business models scale more easily. Some skills compound more rapidly. Some problems, when solved, unlock more value.

Working hard on the wrong thing is still working hard, but it’s a slow form of failure, made worse by the fact that it feels like progress.

I’ve seen this play out countless times. The person spends years perfecting their resume while someone else builds projects that make resumes irrelevant. The startup founder is optimizing their pitch deck while a competitor is just starting to sell. The student memorizes facts while another student learns how to learn.

In each case, the person working harder isn’t necessarily winning. The person with the better strategy is winning, often while working less.

How to Know If You’re Working on the Right Thing

This is the difficult question. How do you know if you’re building typewriters or computers?

Start by asking yourself what would change if you succeeded. If you achieve what you’re working toward, what actually improves? For you, for others, for the world? If the answer is small or unclear, you might be working on the wrong thing.

Look at the trajectory, not just the current state. Where does this path lead in five years if you keep walking it? Are you developing skills that compound? Building assets that appreciate? Creating opportunities that multiply? Or are you just trading time for money, effort for marginal gains?

You Can’t Outwork Meaning

Pay attention to leverage. Some activities give you linear returns. You work one hour, you get one hour of results. Other activities give you exponential returns. You work for 1 hour, and that work continues to generate value for months or years. Writing compounds. Building an audience compounds, learning high-leverage skills compounds. Doing piecework doesn’t.

Notice who’s winning in your field and why. Are they winning because they work harder than everyone else? Sometimes, yes. But more often, they’re winning because they made better strategic choices. They picked a better niche, used a better business model, or developed a more valuable skill. Study their direction, not just their work ethic.

The Role of Effort

None of this means effort doesn’t matter. It absolutely does.

Effort is an amplifier, not a strategy.

If you’re working on the right thing, hard work accelerates your progress dramatically. The person building computers who also works 80 hours a week? They’re going to change the world. The person learning high-leverage skills who practices deliberately for hours every day? They’re going to become exceptional.

If you’re working on the wrong thing, hard work means you get to the wrong destination faster. You become really good at something that doesn’t matter. You build something impressive that nobody needs. You optimize yourself into obsolescence.

The goal isn’t to work less. The goal is to ensure your hard work actually compounds into something meaningful.

Making the Switch

Realizing you’re working on the wrong thing is uncomfortable. Often devastating. You’ve invested time, energy, and identity into a particular path. Changing direction feels like admitting failure.

But sunk costs are sunk. The time you’ve already spent is gone, whether you change directions or not. The only question that matters is where you go from here.

Some signs you need to switch:

You’re working incredibly hard, but the results are marginal. Not because you’re not good enough, but because the thing itself has low leverage.

Other people are achieving better outcomes with less effort. Not because they’re smarter, but because they chose a better game to play.

The path forward requires increasingly heroic levels of effort to maintain your current position. You’re running to stay in place.

You look at people five or ten years ahead of you on your current path, and you don’t want their life. If the destination isn’t appealing, why are you walking toward it?

Making a switch doesn’t mean abandoning everything. Often, it means taking what you’ve learned and applying it to something with more leverage. The skills transfer. The lessons compound. You’re not starting from zero; you’re starting from one.

The Privilege of Choice

There’s an important caveat to all of this. Not everyone has the luxury of choosing what they work on. Financial constraints, family obligations, and systemic barriers are real, and they limit options.

But most people reading this have more choice than they’re exercising. We stay in situations that aren’t working because they’re familiar, because switching is scary, because we don’t want to admit we made a mistake.

The question isn’t whether you have perfect freedom to work on anything. The question is whether you’re using the freedom you do have to move toward better things.

Maybe you can’t quit your job tomorrow, but you can spend your evenings building something with more leverage. Maybe you can’t change careers instantly, but you can start learning skills that open better doors. Maybe you can’t control everything, but you can control your direction.

Hard work is necessary but not sufficient. The direction you work in matters more than the intensity with which you work.

Before you optimize your productivity, make sure you’re working on something worth being productive about. Before you sacrifice more hours, make sure they are directed toward something meaningful. Before you pride yourself on your work ethic, make sure it’s applied to something with real leverage.

You cannot outwork someone who’s working on something better. So instead of just working harder, spend some time figuring out what the better thing is.

Then work hard on that.