Your invisible work matters more than you think.

Your most transformative projects might be the ones gathering dust in a drawer.

There’s a drawer in David Bowie’s archive containing dozens of paintings no one saw during his lifetime. Not because they weren’t good enough to show—some are extraordinary—but because he painted them for himself, with no intention of exhibition, critique, or sale.

In interviews, he described painting as a form of thinking. A way to process ideas that hadn’t yet become songs or concepts or anything with a public purpose. The paintings existed in a consequence-free zone; no career implications, no reputation at stake, no audience to satisfy.

That freedom shaped the work in ways his public projects couldn’t. The paintings were stranger, more exploratory, and more willing to fail. They were thinking of making visible, not performances of artistic competence.

I started keeping what I call a “no-stakes journal” three years ago.

Every other morning, I write three pages that no one will ever read. Not even me; I don’t go back and read old entries. The writing exists purely in the moment of creation, and then it’s done.

The quality of thinking in those pages is different from anything I write for publication. Messier. More honest. More willing to be wrong, confused, or contradictory. Because there’s no consequence to being any of those things.

And here’s what I’ve noticed: ideas that start in the no-stakes journal often become the seed of my best public work. Not because I’m mining the journal for material, but because the consequence-free thinking there allows me to go places I can’t go when I’m writing for an audience.

The work no one sees might be the work that matters most.

Consequence changes everything about creation.

When you create something that will be seen, evaluated, or used, you’re not just making the thing. You’re managing how the thing will be received. You’re thinking about:

Will this be good enough?

What will people think?

Does this serve my goals?

Is this consistent with my brand/identity/previous work?

Will this be criticized?

Does this advance or harm my reputation?

All of those considerations are forms of consequence management. And they shape the work—usually by making it safer, more conventional, and more defensive.

You’re not just creating. You’re creating while simultaneously defending yourself against all possible negative consequences of the creation.

That’s exhausting. And it limits what you’re willing to try.

Work without consequence allows genuine exploration.

When no one will see it, when nothing depends on it, when failure has no cost beyond the private knowledge that you tried something that didn’t work, you can actually explore.

You can follow weird ideas. Test approaches that seem stupid. Combine things that shouldn’t combine. Work in mediums you’re bad at. Attempt things you’re unqualified for.

The bad ideas stay bad. But sometimes, within the permission that no-consequence work creates, you stumble on something genuinely new. Something you never would have found if you were optimizing for public reception.

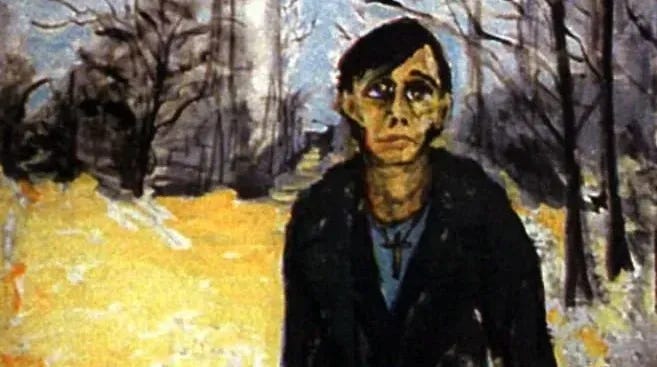

The mathematician Andrew Wiles proved Fermat’s Last Theorem, one of history’s most famous unsolved problems. He worked on it in secret for seven years, telling no one, showing no one his work. Why?

Because he needed freedom from consequence, if the mathematical community had known he was working on it and repeatedly failing, the scrutiny would have been intense. The pressure would have been crushing. The consequences of public failure would have made the exploration impossible.

Only in the consequence-free space of private work could he take the risks necessary to succeed eventually.

Public work optimizes for reception. Private work optimizes for truth.

This is the fundamental difference. When you’re creating for an audience—even a loving, supportive one—part of your brain is running an audience simulation. What will they think? How will they react? What do they expect?

That audience simulation shapes your choices. Sometimes, it helps you communicate clearly, consider the impact, and refine rough ideas. But it also constrains; you're prevented from going places the imagined audience might not follow.

Private work has no audience simulation. You can follow the idea wherever it goes without checking whether anyone else would find the destination interesting or valuable.

That’s where you encounter truth: your actual thoughts, unmediated by performance. The things you really think before you’ve shaped them into what you think you should think.

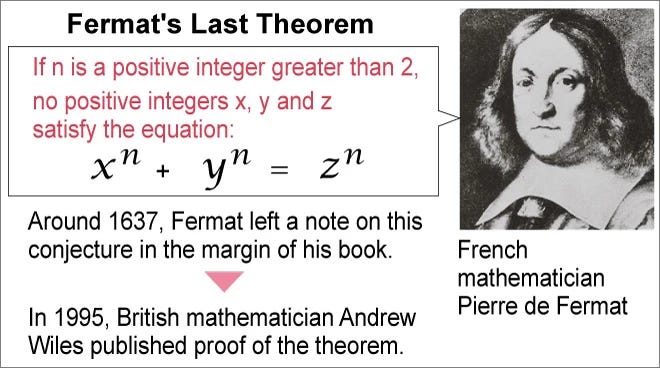

Anaïs Nin kept diaries her entire life. The published versions are fascinating, but she described them as fundamentally different from the unpublished portions. The published diaries were written with the audience in mind, shaped for readability, and curated for impact.

The unpublished portions were raw thinking, contradictory, uncertain, sometimes ugly, and completely honest.

She wrote, “We write to taste life twice, in the moment and in retrospect.” But retrospect requires the honest capturing in the moment, without consequence.

The pressure of consequence breeds self-censorship.

Not just obvious censorship, but also avoiding topics that might offend or hurt. Subtle censorship: softening edges, qualifying statements, avoiding vulnerability, performing confidence you don’t feel, and pretending certainty when you’re confused.

All of this happens semi-consciously when you know the work will be seen. You’re protecting yourself from judgment, misunderstanding, criticism, and exposure.

In consequence-free work, those protections drop. You can write what you actually think, including all the parts you’re not sure about. You can be wrong loudly. You can expose confusion without shame.

That undefended thinking is often more valuable than the defended version because the defense is where authenticity goes to die.

Some of your best ideas will come from consequence-free exploration.

Not because the work itself is publishable; usually it isn’t. But because the thinking process in that work takes you places that consequential thinking can’t reach.

Then later, when you’re working on something public, you remember an idea from the private work. Or you recognize a pattern you first noticed in the no-stakes exploration. Or you have the confidence to try something unusual because you already tested it privately.

The consequence-free work becomes the research and development for your public work. It doesn’t directly convert to output, but it enriches everything else you make.

Creating without consequence is training for creative courage.

When you practice following ideas without worrying about the outcome, you’re training a muscle. The ability to explore without immediately evaluating. To try without immediately judging. To make without immediately measuring.

That muscle atrophies when every creation has stakes. You forget what it feels like to… make something without all the meta-level concerns about whether it’s good enough.

Then, when you need creative courage for a public project, when you need to take a real risk on something unusual, you have no practice. You’ve only ever created defensively.

The no-consequence work is where you practice bravery when it costs nothing. So that when you need to be brave publicly, you’ve already learned how it feels.

The paradox: the work no one sees might be the most important work you do.

Not important because of impact, it has none, by definition. Important because of how it shapes you as a creator.

It keeps you connected to why you create in the first place, before you built a career, reputation, or audience. It reminds you what it feels like to make something purely because you’re curious what will happen.

It prevents your entire creative practice from becoming performative. If everything you make is for someone else, you lose touch with your voice. You forget what you think when no one’s listening.

The consequence-free work is how you stay in a relationship with yourself as a creator, not just as a performer of creation.

How to create consequence-free space:

The point isn’t that you need a literal drawer of secret work. It’s that you need some space in your creative practice where consequence doesn’t govern.

That might be:

Morning pages no one reads, including you

Sketchbook work that never becomes finished pieces

Music you play alone that never gets recorded

Writing in a private document you’ll never publish

Projects under a pseudonym so they don’t affect your reputation

Experiments in mediums where you have no audience and no expertise

The specific form doesn’t matter. What matters is creating a space where you can fail, be messy, be wrong, be confused, and be weird without any cost beyond the private knowledge that you tried something.

The resistance to consequence-free work is that it feels wasteful.

If no one sees it, what’s the point? Isn’t that time better spent on work that might actually reach people or advance your goals?

But that calculation assumes that creation is valuable only for its outputs. That is the only point of making something: what happens after you’ve made it.

Consequence-free creation is valuable for what happens during the making, for how it changes you as a thinker and creator. For the space it creates for exploration, that consequential work can’t allow.

The work no one sees isn't a waste. It’s the composting that makes the garden possible.

When you’re feeling stuck in your public work, when everything you make feels safe and conventional, when you’ve lost touch with what you actually want to say, that’s when you need consequence-free space most.

What could you make if no one would ever see it? What would you try if failure had no cost? What would you explore if you didn’t have to defend, explain, or justify?

Make that not instead of public work, but alongside it. Let yourself have space where consequence doesn’t govern every choice.

The work no one sees might be the work that teaches you everything you need to know to make the work everyone sees worth looking at.